Leave my country. I dunno wtf you are talking about. Just get the fuck out of Canada.You asked me for the questions...I gave them to you after you kept crying about it....now you refuse to answer them and call me names.

Only cowards and losers do that when they have been exposed.

In your case, it was easy.

2 Israeli Embassy staff members killed in shooting near Jewish museum in DC, officials say

- Thread starter canada-man

- Start date

Amazing how many people on this board think its perfectly reasonable to burn 9 children alive because you were trying to murder a doctor.Whatever, dude.

The nazis blamed the Jews too.

Its the same, you are justifying genocide and there is no level of genocide you won't say is wrong.

Not burning a little girl to death in the school she was sheltering in with her family.

Not starving 1 million children to death, not bombing every school, hospital and dropping 36kg of explosives for every person in Gaza.

You cannot say Hamas is so evil that it justifies worse evil and claim to have a moral standing.

You are pathetic for defending burning this girl to death.

Last edited:

Its an amazing chain of evil, really.Amazing how many people on this board think its perfectly reasonable to burn and entire apartment of 9 children alive because you were trying to murder a doctor.

They think its ok to starve 2 million people to try get to 20,000 militants, they think its ok to burn children to death and destroy a hospital/school to try to murder a doctor who wasn't a militant in order to control the indigenous population and try to get them to stop resisting while they destroy their homes and steal their land.

Netanyahu describing a concentration camp.

Masha Gessen in the NYTimes Today

Even Israel’s massacre in Gaza, which makes Russia’s warfare in Ukraine look restrained, can’t produce new headlines after more than 19 months of indiscriminate bombing and warfare by starvation. It is news when two Israeli Embassy employees are murdered in Washington, D.C. But when entire Palestinian families are killed, or when Palestinian children die of malnutrition, it’s just another day in Gaza. Nor is it news that the U.S. government is indifferent to war crimes committed by its allies.

In this country, too, fewer and fewer things can surprise us. Once you’ve absorbed the shock of deportations to El Salvador, plans to deport people to South Sudan aren’t that remarkable. Once you’ve wrapped your mind around the Trump administration’s revoking the legal status of individual international students, a blanket ban on international enrollment at Harvard isn’t entirely unexpected.

Once you’ve realized that the administration is intent on driving thousands of trans people out of the U.S. military, a ban on Medicaid coverage for gender-affirming care, which could have devastating effects for hundreds of thousands, just becomes more of the same. As in a country at war, reports of human tragedy and extreme cruelty have become routine — not news.

At the end of Molochnikov’s play, the main character, Kon, loosely based on the director himself, speaks on the phone to his mother, a famous actress, who stayed in Moscow when Kon left. In the three years since the full-scale invasion, she has adjusted and, most important, she is working.

Almost matter-of-factly, she informs her son that his friend, a poet who spoke out against the war, has died in prison. Kon is inconsolable. “Mama, they killed him,” he says. The mother tells him not to worry about missing the funeral and to go to his own birthday party: “They have such good parties in America. Isn’t a birthday party better than a funeral, anyway?”

She is not heartless, just realistic. Reasonable people know the rules and live within the confines they dictate.

We humans are stability-seeking creatures. Getting accustomed to what used to seem unthinkable can feel like an accomplishment. And when the unthinkable recedes at least a bit — when someone gets released from detention (as the Columbia University student Mohsen Mahdawi was a few weeks ago) or some particularly egregious proposal is withdrawn or blocked by the courts (as the ban on international students at Harvard has been, at least temporarily) — it’s easy to mistake it for proof that the dark times are ending.

But these comparatively small victories don’t alter the direction of our transformation — they don’t even slow it down measurably — even while they appeal to our deep need to normalize. They create the sense that there is more air to breathe and more room to act than there was yesterday.

And so just when we most need to act — while there is indeed room for action and some momentum to the resistance — we tend to be lulled into complacency by the sense of relief on the one hand and boredom on the other.

Think of the trajectory of the so-called travel ban during Trump’s first term. Its first iteration drew thousands into the streets. The courts blocked it. The second iteration didn’t attract nearly as much attention, and most people didn’t notice when the third iteration of the travel ban, which had hardly changed, went into effect. Now Trump’s administration is drafting a new travel ban that targets more than five times as many countries.

It took Alexander Molochnikov two and a half years to put on “Seagull: True Story.” The process was arduous and often frustrating, he told me, but the long journey was ultimately good for the play. It allowed him to observe the normalization of the war in Russia and include these observations in the text. It also enabled him to get to know the United States.

The second act takes place in New York. One character, a sleazy producer, observes: “Just think. When he first came to this country, he was afraid even to say he is Russian. And now we are all friends and making peace everywhere in the world. Such a good peace.”

At one point, another character makes a comment about censorship and adds: “Something like that could never happen in America. Right?” On the night I saw the play, the audience laughed a kind of laugh I’d heard before, but not in this country: It was bitter, and it was resigned.

Even Israel’s massacre in Gaza, which makes Russia’s warfare in Ukraine look restrained, can’t produce new headlines after more than 19 months of indiscriminate bombing and warfare by starvation. It is news when two Israeli Embassy employees are murdered in Washington, D.C. But when entire Palestinian families are killed, or when Palestinian children die of malnutrition, it’s just another day in Gaza. Nor is it news that the U.S. government is indifferent to war crimes committed by its allies.

In this country, too, fewer and fewer things can surprise us. Once you’ve absorbed the shock of deportations to El Salvador, plans to deport people to South Sudan aren’t that remarkable. Once you’ve wrapped your mind around the Trump administration’s revoking the legal status of individual international students, a blanket ban on international enrollment at Harvard isn’t entirely unexpected.

Once you’ve realized that the administration is intent on driving thousands of trans people out of the U.S. military, a ban on Medicaid coverage for gender-affirming care, which could have devastating effects for hundreds of thousands, just becomes more of the same. As in a country at war, reports of human tragedy and extreme cruelty have become routine — not news.

At the end of Molochnikov’s play, the main character, Kon, loosely based on the director himself, speaks on the phone to his mother, a famous actress, who stayed in Moscow when Kon left. In the three years since the full-scale invasion, she has adjusted and, most important, she is working.

Almost matter-of-factly, she informs her son that his friend, a poet who spoke out against the war, has died in prison. Kon is inconsolable. “Mama, they killed him,” he says. The mother tells him not to worry about missing the funeral and to go to his own birthday party: “They have such good parties in America. Isn’t a birthday party better than a funeral, anyway?”

She is not heartless, just realistic. Reasonable people know the rules and live within the confines they dictate.

We humans are stability-seeking creatures. Getting accustomed to what used to seem unthinkable can feel like an accomplishment. And when the unthinkable recedes at least a bit — when someone gets released from detention (as the Columbia University student Mohsen Mahdawi was a few weeks ago) or some particularly egregious proposal is withdrawn or blocked by the courts (as the ban on international students at Harvard has been, at least temporarily) — it’s easy to mistake it for proof that the dark times are ending.

But these comparatively small victories don’t alter the direction of our transformation — they don’t even slow it down measurably — even while they appeal to our deep need to normalize. They create the sense that there is more air to breathe and more room to act than there was yesterday.

And so just when we most need to act — while there is indeed room for action and some momentum to the resistance — we tend to be lulled into complacency by the sense of relief on the one hand and boredom on the other.

Think of the trajectory of the so-called travel ban during Trump’s first term. Its first iteration drew thousands into the streets. The courts blocked it. The second iteration didn’t attract nearly as much attention, and most people didn’t notice when the third iteration of the travel ban, which had hardly changed, went into effect. Now Trump’s administration is drafting a new travel ban that targets more than five times as many countries.

It took Alexander Molochnikov two and a half years to put on “Seagull: True Story.” The process was arduous and often frustrating, he told me, but the long journey was ultimately good for the play. It allowed him to observe the normalization of the war in Russia and include these observations in the text. It also enabled him to get to know the United States.

The second act takes place in New York. One character, a sleazy producer, observes: “Just think. When he first came to this country, he was afraid even to say he is Russian. And now we are all friends and making peace everywhere in the world. Such a good peace.”

At one point, another character makes a comment about censorship and adds: “Something like that could never happen in America. Right?” On the night I saw the play, the audience laughed a kind of laugh I’d heard before, but not in this country: It was bitter, and it was resigned.

What are you so afraid of? Answering a few simple questions?Leave my country. I dunno wtf you are talking about. Just get the fuck out of Canada.

Or just trolling like a coward Frankfooter?

IneffectualWhat are you so afraid of? Answering a few simple questions?

Or just trolling like a coward Frankfooter?

Everything I said there is factual and verifiable.Living in a world of fiction.

They got their country -modern day Jordan.The brits promised Palestinians their country back in exchange for support in WWII.

They lied.

At the time, the Jewish population was only 7%.

Before the zionist colonization.

When will you finally realize what you've been backing?

In 1939 just before WWII the Jewish population in 'Palestine' was 30%, not 7%. Get your facts straight Jack.

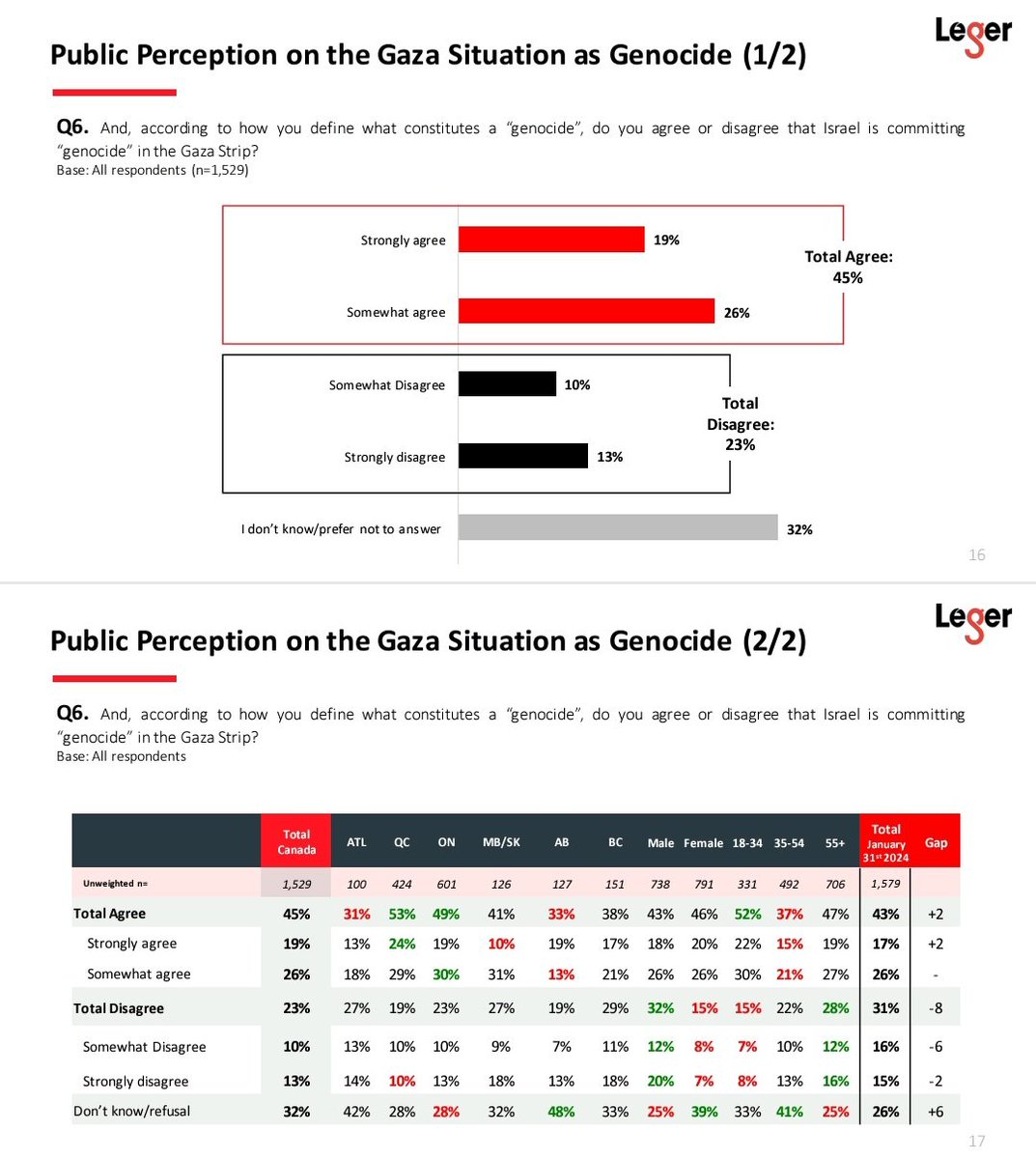

Just because people believe something doesn't make it true. The people saying yes don't even know what the definition of genocide is.One year ago, 45% of Canadians believed Israel is committing genocide.

Thing those numbers have gone down?

Zionists won't admit that they are the racist minority here.

Many legal experts have established said it meets the established criteria. :the deliberate killing of a large number of people from a particular nation or ethnic group with the aim of destroying that nation or group.Just because people believe something doesn't make it true. The people saying yes don't even know what the definition of genocide is.

What more do you need to know?

Except it’s not.Everything I said there is factual and verifiable.

Yes of course. It's only a genocide when it's done to a certain group. Not when it's done by them.Just because people believe something doesn't make it true. The people saying yes don't even know what the definition of genocide is.

Their country is Palestine, you can't give them a different country that already exists and say its their's.They got their country -modern day Jordan.

In 1939 just before WWII the Jewish population in 'Palestine' was 30%, not 7%. Get your facts straight Jack.

Oh wait, that's the entire rationale of zionism, that the brits gave them land owned by Palestinians.

Of course you think that's the way it works.

Just like you can't kill children and call it self defence.

The ICC, ICJ, UN are all very clear on the definition of genocide.Just because people believe something doesn't make it true. The people saying yes don't even know what the definition of genocide is.

Its the people trying to justify genocide that keep trying to bend the definition so they don't have to admit they are like nazis.

Likely Paul Bernardo didn't think what he did was murder too.

How soon until they all say they were against it all along?